Divers on the shores of Guatemala's Caribbean Coast. Credit: FUNDAECO

An impressive amount of species living across Guatemala are endemic, meaning they aren’t found anywhere else in the wild. This includes 15% of terrestrial vertebrate species and nearly 13% of the country’s plant species. The country’s rainforests host much of this wildlife, making them one of Central America’s biodiversity hotspots. Guatemala’s name itself stems from the Aztec Náhuatl term Quauhtlemallan, meaning ‘land of many trees’. Today though, just 20% of Guatemala’s lowland rainforests remain. WLT partner, Foundation for Ecodevelopment and Conservation (FUNDAECO) has been working for 33 years to restore, protect and conserve Guatemala’s species-rich Caribbean coastal ecosystems.

Philip Shapiro, WLT Trustee, had a pivotal role in helping FUNDAECO protect more habitat on the Caribbean Coast. In this interview, we learnt about Philip’s recent visit to the region, his encounters with marine life, and the impacts of donations for people, wildlife, and biodiversity.

WLT: What was the purpose of your visit to WLT partner FUNDAECO in Guatemala?

Philip: In 2021, I made a donation to WLT to help FUNDAECO acquire land to extend the Laguna Grande Reserve (Laguna is Spanish for lagoon). My trip involved visiting the lagoon I helped protect and surrounding tropical lowland rainforests and mangroves. As someone who loves the sea, it can sometimes be quite tricky to help make an impact as an individual donor on marine life. Property relations governing the sea differ to those on land. As an experienced diver and marine photographer, I was therefore happy to be supporting FUNDAECO in their project which benefits both marine and land environments. I was also excited to see how its “ridge to reef conservation strategy” works in practice.

Laguna Grande is a vital breeding area for the Vulnerable West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus). Credit: Philip Shapiro

WLT: Tell us a bit about the places you explored and what was happening there?

Philip: Starting from FUNDAECO’s head office in the capital, Guatemala City, we travelled out to Laguna Grande in the Izabal region. Traversing the coastline, I counted numerous inlets etched into the coastline carrying water from the lush, green landscape out to the sea. I was reminded of the powerful origin story of the Laguna Grande Reserve. Originally, the area was bought by a logger who wanted to clear the forest for timber. However, due to financial issues, they eventually had to sell some of their land to the bank, allowing FUNDAECO to then purchase this land with WLT funding from donors such as myself.

After visiting Laguna Grande, we later travelled to Tapon Creek – another habitat that FUNDAECO helps to preserve. Here, the mangroves and damp forests open up into numerous gloriously white sandy beaches, from which we saw dolphins gliding through the water. This coastline is vulnerable to urban development for hotels and houses. It’s therefore vital that FUNDAECO protect it.

FUNDAECO’s ‘ridge to reef’ strategy keeps coastal ecosystems healthy by addressing environmental degradation inland. Credit: Philip Shapiro

WLT: Marine life is central to the work of FUNDAECO – what encounters with the sea did you have?

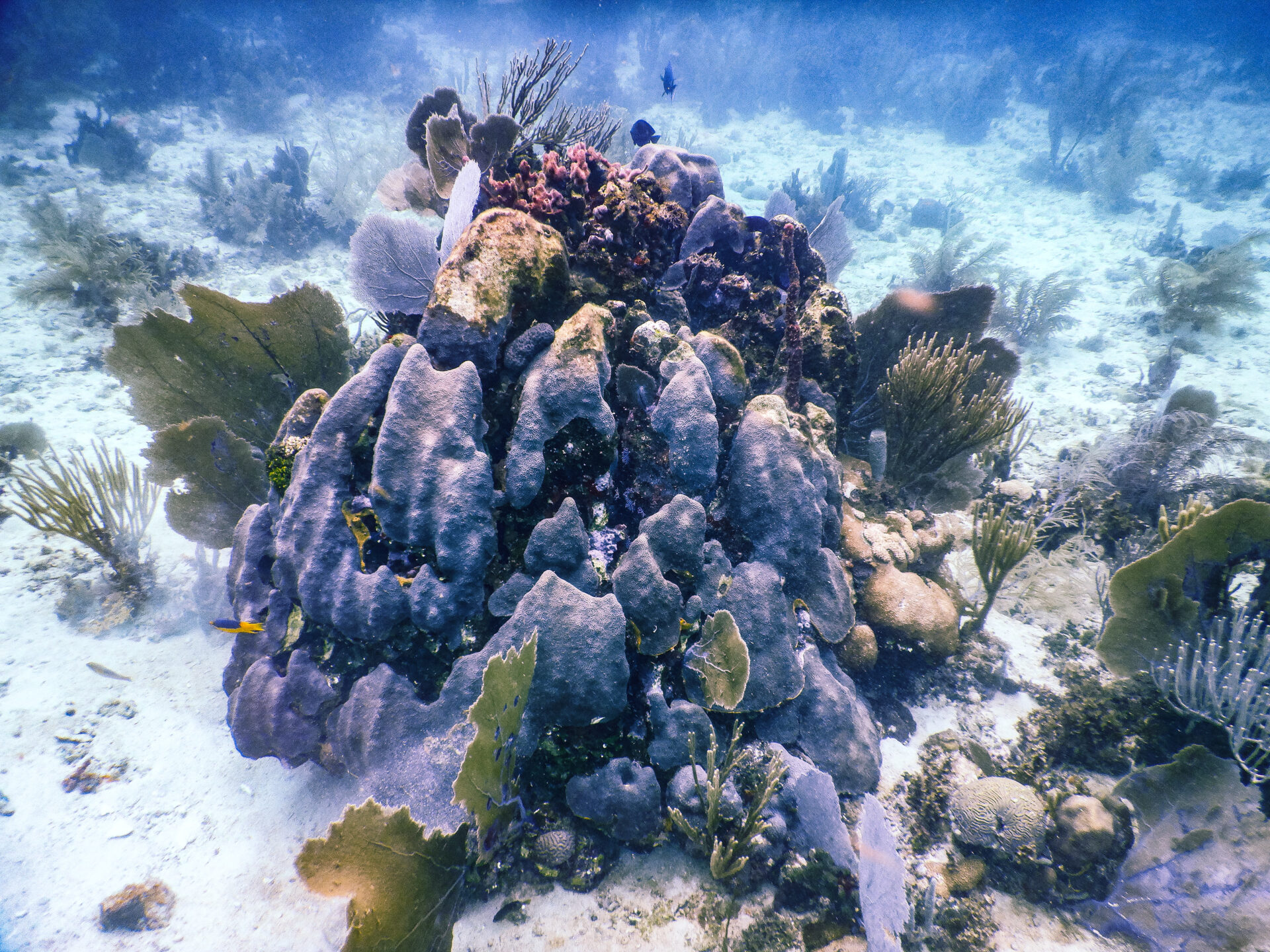

Philip: We went to a coral reef off Guatemala’s coast called Corona Caimán (Cayman Crown) and when we dived down there it was simply incredible – amidst the stunning colours of the coral we saw Barrel Sponge (Xestospongia muta) and several species of Angel Fish. We then went to a second marine site which hadn’t been properly explored yet. When we swum amongst the reef, it soon became clear that the quality of this coral reef was, in many ways, in better condition than that of Corona Caimán. It was fun to be part of this sort of ‘discovery’ of a reef system for which – I later was told by FUNDAECO – they’re going to apply for conservation status. It’s very exciting.

Coral diversity in the Corona Caimán reef, thought to be Mesoamerica’s best-preserved coral ecosystem. Credit: FUNDAECO

WLT: Alongside your marine life encounters, did you see many wild animals on land?

Philip: In the rainforest the animals often heard us coming and tended to steer out of our way. We did see a troop of Howler Monkeys (Alouatta pigra) making their iconic calling sounds reminiscent of dinosaurs (or what I imagine they sounded like based on Jurassic Park!). We also saw lots of interesting bird life too, including numerous hummingbird species, Montezuma Oropendola (Psarocolius montezuma), and Red-capped Manakin (Ceratopipra mentalis). I would love to say a Jaguar walked across our path, but sadly this didn’t happen, although we did spot a Jaguar footprint which was very cool!

One of the Howler Monkeys which followed Philip through the forest canopy. Credit: Philip Shapiro

WLT: How did it feel knowing you played a part in the protection of these species’ futures and their habitat?

Philip: To stand there and see the Laguna Grande sign alongside the World Land Trust name was quite emotional actually. Especially knowing I am partly responsible for keeping safe the amazing flora and fauna that was around me. When you hear the story about how the land was going to be logged, it made walking through this grand forest feel all the more powerful. Surrounded by the gushing sounds of water everywhere we turned, I couldn’t help but wonder: without my own and other donor’s funding, what would have happened to this habitat and its biodiversity? No doubt it would have been sold by the bank to someone else – perhaps with extractive intentions, or even completely felled or converted to pasture. This ecosystem is now secure because of something I helped do.

Water is a precious life force in the Izabal region of Caribbean Guatemala. Credit: Philip Shapiro

WLT: What did you learn from being there; did anything surprise you or offer you distinct perspectives?

Philip: I learnt so much! I saw how FUNDAECO’s purpose was not only to protect nature, but also to improve outcomes for poverty-affected and marginalised people – especially indigenous people, women, and young people. I witnessed the importance of gaining trust from local people, something FUNDAECO had done from its establishment and continues to do through including and sharing benefits of its conservation programmes. Widespread poverty in the area means you cannot expect everyone to think about conservation in the same way. But thanks to FUNDAECO’s support, microbusinesses and ecotourism businesses which help the environment have succeeded.

WLT: Global leaders have not given the biodiversity crisis the attention it warrants, nor are they responding to the climate crisis with the urgency it needs. Given this, what brings you hope for the future of nature conservation?

Philip: I get hope from seeing people in action who are truly making sustainable conservation models work. What FUNDAECO has achieved in Guatemala is really inspiring, bringing diverse local communities into the project. Biodiversity is rising on the political agendas and growing in importance. However, in the absence of concrete political action on biodiversity, I think it will have to be NGOs which take the lead. I think FUNDAECO is such a great example of this. For over 30 years, it has achieved so many meaningful outcomes whilst bringing local communities along their journey. If they can do it there, then there is hope for the world.

Angel Fish species are part of the vast aquatic biodiversity living in the waters of Guatemala’s Caribbean Coast. Credit: FUNDAECO

The single most effective action we can take to mitigate global warming is to avoid further loss of forests, particularly in the tropics. The Laguna Grande Nature Reserve is part of WLT’s Carbon Balanced programme which protects life-sustaining forests, particularly mature ones, to store and sequester carbon.

Click here to find out more about Carbon Balanced and how you can support our participating partners.